Straight to Hell: the Marriage of John Custis and Frances Parke in Colonial Virginia

While many of you have heard of Arlington, the Virginia military cemetery across the Potomac River from Washington, DC, not everyone knows there was an earlier Arlington.

Arlington Cemetery derives its name from Arlington House, which was once the property of Mary Randolph Custis, an intellectual who spoke Latin and Greek, understood politics exceptionally well and was a lifelong voracious reader.

She married Robert E. Lee in 1837 at Arlington House, her parents’ home.

Her father bought the riverside property and built Arlington House, thinking of his ancestral home in remote Northampton County, Virginia, leaving it to Mary in 1857.

Arlington in Northampton County was built in the seventeenth century by John Custis II after marrying Tabitha Scarburgh, a daughter of landowner Col. Edmund Scarburgh and a niece of Sir Charles Scarburgh, mathematician, translator and Chief Physician to Charles II.

Her father Edmund was known to be unscrupulous and amassed a fortune in Virginia, one reason Custis married her. As it turned out, Tabitha was known to quarrel with Custis over how he spent her money.

Custis ignored his wife and built the first Arlington, a three storey brick house.

He had his children with a previous wife, including son John Custis III; his grandson was John Custis IV.

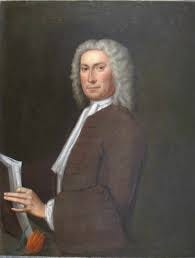

John Custis IV (1678–1749) was often referred to as John Custis of Williamsburg, (or Major Custis) to distinguish him from other men with that name in Northampton County.

While remembered as Martha Washington’s first father-in-law (she married George Washington as a widow with two children), Custis really ought to be remembered as a most colourful character.

He married Frances Parke in 1706, for her money and social connections: her father had served as aide-de-camp to the Duke of Marlborough and was Governor of the Leeward Islands, appointed by Queen Anne.

It was a marriage made in Hell: they quickly grew to loathe one another. An enslaved manservant named Pompey was given the unfortunate task of running between Custis and his wife to deliver messages when they stopped speaking to one another.

Frances had not seen much of her father for years. Parke served as an aide-de-camp the Duke of Marlborough during the War of Spanish Succession, achieving a level of fame when dispatched to Queen Anne to apprise her of Marlborough’s victory at Blenheim. And he received a reward: in 1705, Queen Anne made Parke chief governor of the Leeward Islands, a deep disappointment: he wanted to be governor of Virginia.

Perhaps Her Majesty had been apprised of his quick temper. And he could be violent, said to “have horsewhipped the governor of Maryland after challenging him to a duel”. On another occasion, dragged a Virginia minister’s wife from a pew in a fit of anger.

Given lemons, Parke resolved to make lemonade, doing his best on Antigua “to regulate the garrison regiment, modernize the island militia, and fortify the capital, St. John's.” But James Jones, the 38th Regiment’s new commander, blocked Parke at every turn. Jones had his position thanks to an enemy of the Duke of Marlborough: the idea was to “undermine” Marlborough further - he had declined in power - by making Parke appear utterly useless.

Jones may have spread a rumour that Parke was guilty of “debauching many of the wives and daughters” of English planters on Antigua. While certainly promiscuous, Parke was attractive to women, as his mistress (and mother of his daughter) knew full well.

Then came the events of 7 December 1710.

James Jones may very well have whipped militiamen into a frenzy. Storming the governor’s mansion, they quickly found Parke. He defended himself ably, reportedly wounding more than one of his attackers, but was soon overwhelmed. Stripped naked, he was dragged from his house, beaten, shot and possibly stabbed for good measure. Then, predictably, the mob looted his house. And according to oral history, “his body was left in the streets for a week to rot after his murder.”

Most of his bodyguards, grenadiers of the 38th Regiment, were killed by the mob as well. No one was ever arrested, much less prosecuted for the murders. Marlborough was told what happened and while he could do little, made certain that each and every militiaman implicated in Parke’s murder never served again.

Parke was over £3,000 in debt when he was murdered. His estate “in chaos”, the will divided his Virginia and Caribbean properties between his three daughters: Frances Parke Custis, Lucy Parke Byrd and Frances Russell, daughter with his mistress Catherine Chester. Decades of legal woes would follow, the burden of the debts falling heavily on his heirs, particularly on Frances and her husband John Custis.

By June 1714, having endured eight years of marriage, they had a lawyer draw up articles of agreement. Among other things, Custis agreed to provide for Frances and their children, Daniel Parke Custis and his younger sister Frances. And he promised to let her run their household as she saw fit, provided she refrained from calling him “vile names” and did not “give him any ill language.”

He hoped they would be more “loving” to one another. But he maintained his silence. Great-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, tactfully commented that the marriage was one in which “connubial bliss was short”.

So Frances was astonished when Custis asked her one day if she would like to go for a carriage ride. Despite her reputation as “shrewish”, Frances was most agreeable when approached politely: she replied that she would be delighted to, but asked why. And where they were going.

She received no reply. So Frances held her tongue and got into the carriage.

They drove in silence until Frances could stand it no longer: “Where are you going, Major Custis?

“Straight to Hell, Madam,” Custis growled.

Frances was completely unfazed. “Drive on, Sir! Any place is better than Arlington.”

She maintained her composure even when Custis turned sharply off the road and drove the carriage towards the Chesapeake Bay. Frances maintained her composure as Custis drove on, water rising. The horse began to swim.

“Where are you going, Major Custis?”

When told again that he was going straight to Hell, she encouraged him.

“Drive on! I am not afraid to go where you will go,” adding: “The Devil will be cheated of [one of] his own until he gets you.”

Custis looked at his wife before replying. “The Devil, Hell and nothing else will scare you, so I might as well return.” So Custis got the carriage out of the sea and drove home to Arlington.

Frances Parke Custis died of smallpox at Arlington the following March.